What happened?

Global IT outage hits 8.5 million devices – causing $1.5 billion in damages and major service disruptions

The world woke up on Friday morning to the biggest IT outage in history. A faulty software update by cybersecurity company CrowdStrike took down 8.5 million Microsoft-powered devices worldwide, resulting in an estimated $1.5 billion in damages to the global economy. The incident affected critical public infrastructure, leading to the cancellation of 2,400 flights, the unavailability of security helplines such as 911, and the failure of payment systems, forcing customers to revert to cash for their daily purchases.

While CrowdStrike has issued a fix and Microsoft has released a recovery tool that will eventually restore normality for most businesses over the next few days, the entire industry is now faced with the question of how to reduce vulnerability and strengthen the resilience of critical support infrastructure amid an increasingly digital and interconnected global society.

The Danger of Connected Systems

-

While this incident is serious, it could have been much worse, as only 1% of all Windows-operated devices were affected, and many global systems run on an open Linux base. That said, while only 1% of PCs were affected, these had a cascading effect, as systems are closely connected in the global economy, allowing damage to spread outside the infected hosts. For example, although Apple devices were not directly affected, Apple Pay also ceased to work for multiple customers and merchants, as the authentication systems of TD Bank, Chase, Wells Fargo, and Bank of America were impacted.

A Closer Look at Payments Infrastructure

Understanding the impact of recent technology outages on in-person payments

Due to its global impact and visibility, the CrowdStrike incident is by far the most prominent example of a technology outage, but it is not the only one. The payments value chain has been hit several times with outages over the last couple of years, with in-person payments proving to be the Achilles' heel of the industry.

Germany: In May 2022, terminals from a well-known terminal provider ceased to operate due to a software update that had not been properly rolled out to devices already past their normal lifecycle. These devices still powered the retail ecosystems of major German retailers such as Aldi, Netto, and Rossmann. Operations were only restored after devices were physically exchanged, a process that lasted several weeks.

Netherlands: Earlier this year, the country experienced a three-hour payment system outage by the dominant processor, resulting in up to 40% of PIN-based transactions failing. This affected major retailers such as Albert Heijn, Jumbo, and McDonald's.

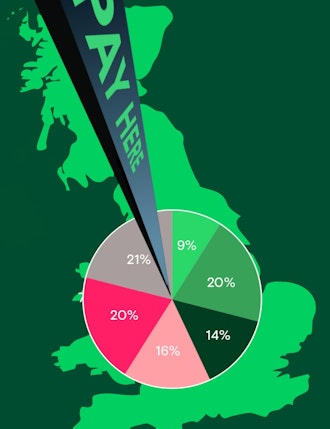

UK: Shortly after the Netherlands incident, the UK experienced a system outage just days before CrowdStrike alerted the world about the potential instability of global tech infrastructures outside the much-discussed cybersecurity threat, hindering retailers across the country from accepting card transactions.

Despite being minor and local, these incidents follow a similar pattern to the CrowdStrike one and point to similar root causes. The high-security nature of certain industries, such as public transport, banking, or public safety infrastructure, favoredfavoured a rigid design with a limited number of responsible key players. While these processes used to work in simpler times, with software being deployed and upgraded manually, they are less efficient in times of over-the-air updates and highly connected cloud-based systems. Though many of the processes have been digitally enabled, their fundamental design is still deeply rooted in the analog world, seeing processes as one-way streets handled by a single provider, limiting choice and flexibility, but even more, installing potential points of failure into the ecosystem.

It may seem paradoxical, but the secure designs of the past now pose significant risks to today's digital ecosystems, creating potential weak points in an otherwise flexible and resilient environment. Take payment terminals, for instance. The card acceptance process, developed in the 1950s, prioritised security and speed over connectivity and data. Despite the digital transformation in commerce, this system has remained largely unchanged for 70 years. Today's physical terminals are still hardcoded to a single processor, rendering them highly vulnerable on both the terminal and processor sides, as demonstrated by recent disruptions in Germany, the Netherlands, and the UK.

“Traditional payment terminals were built for security, but their outdated design now created big vulnerabilities in our modern digital world, as seen in recent outages across Europe.”

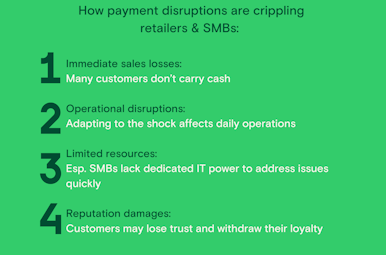

The ones who suffer are the retailers, especially the SMBs. Not only do they lose immediate sales, as many customers do not carry cash with them, but they also have to bear operational disruptions as they adapt to the shock. While bigger retail chains have their own IT departments managing their POS environment and have the market power to trigger action with the respective providers, SMBs are at the receiving end, as they lack the knowledge and power to instill action, leaving them only with the option to revert back to cash until they are up for an upgrade. Nevertheless, what both retailers and the entire value chain share is reputational damage and therefore a lack of customer trust. The ability to accept cashless payments is becoming increasingly important in a digital economy that sees far more customers interacting with self-checkout terminals. One just has to look at “Pay at Pump” or EV-charging scenarios to recognize the importance of being able to accept payments, let alone realizing the impact a missed sale makes for a small mom-and-pop shop.

A problem too big to solve?

The fundamental problem with security-driven processes, besides from their outdated design, is their complexity. Many find them too challenging to modernizse digitally, leading to a tendency to overlook the problem, defer to specialized partners, and maintain the status quo. This all works well until something like last Friday happens, with the “Blue screen of death” indicating to the world that something went seriously wrong.

Strategies for preventing and containing failures in payment systems

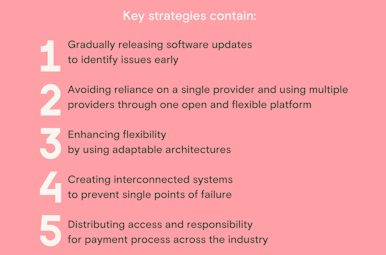

Rather than just lamenting on things that happened, let’s focus on how to prevent them in the future or, if they do occur, how they can be contained and prevented from spreading within the environment. For that, let us start with the obvious learning from the recent CrowdStrike event. Software deployment should follow a staggered approach, with the update being released to a limited number of client systems first and then incrementally rolled out to other clients, especially when the update does not address any immediate critical issues. This allows the provider to gain experience with their software on devices in the field.

Nevertheless, what is even more important is to address the fundamental design challenge that security-driven processes have, which concentrates power and potential friction points into the hands of a few core providers, creating monolithic system environments and rigid processes. In the case of the in-person payment process, this is the terminal and the processor, making the non-cash payments process predominantly a rigid one-way street communication. If either of those two players is down, for example, through a software update gone wrong, hardware malfunction on the terminal side, or a processor becoming unavailable because of a power outage, cybersecurity incident, or internet outage, the entire non-cash payments process no longer works for merchants.

Therefore, the industry needs to diversify, providing more choice, standards, and flexibility regarding terminal providers, IT architecture, supported payment methods, and connected processors. This will turn the traditional one-way street design into a connected cashless payment highway. Furthermore, providing democratic access to the payment terminal will further distribute ownership over the card-acceptance process, and with ownership comes responsibility. The in-person payments process today is too complex and limiting for almost any industry player to tackle individually, so most industry players gave up a long time ago, just accepting its limitations. But mere acceptance is the opposite of taking responsibility.

In-Person Payment Orchestration to the Rescue

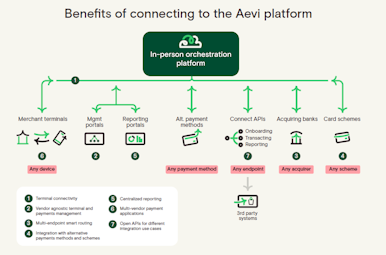

While online payment orchestration is already an established term in the payment industry, “in-person payment orchestration” is less heard of. The reason for that is that it tackles exactly the complexity that many stakeholders of the payment value chain have shied away from. It provides choice regarding both terminal and processing backend providers and flexibility in relation to payment methods accepted on the device, leveraging a managed micro-service architecture in combination with open standards such as ISO 20022 and Android. It does so by providing a cloud-based integration layer that logically separates endpoint management across device types and brands from payment processing and the highly secure payment environment from the more open world of data processing.

The combination of these factors enables any player in the payment value chain to assume responsibility over their own devices, offering oversight and insight across estates and transactions to an individual provider and a highly resilient ecosystem for the entire industry.

Ensuring payment resilience with in-person payment orchestration:

- If a processor is down, the system can revert to either offline mode, bridging short interruptions, or switch directly to another processor in failsafe mode.

- It allows merchants to accept other forms of cashless payments and alternative payment methods, such as PayPal, Venmo, or Alipay, providing options for an increasingly cashless society.

- Terminal estates can be monitored centrally across connected brands, allowing the process owner to provide health checks on devices and enabling over-the-air provisioning and updates in a staggered way.

- If a terminal experiences a malfunction that cannot be fixed via a software update, providers no longer need to wait for a fix from the same terminal manufacturer but can switch to another brand.

- In the meantime, the merchant can still accept payments by reverting to SoftPOS solutions that work on regular phones.

Additionally, properly designed in-person payment orchestration systems mitigate the risk of single points of failure by spreading transactions across multiple providers. The global cloud infrastructure with built-in redundancy ensures (offline) payment processing as well as store-forward and failsafe routing, even if processors are down.

In-person payment orchestration updates the analog design of terminal-based payment acceptance to the digital age, making the card-present process as flexible as the card-not-present one, providing choice, flexibility, and ownership. Will it be a 100% guarantee against outages? No, nobody can make such a promise. However, it dramatically reduces the chance of this happening, limits spreading and cascading, and even if it does hit, provides alternative routes of acceptance. A robust platform handles high volumes of transactions without compromising performance or quality, keeping businesses running smoothly no matter what. Diversity and digital resilience are the answers!

If you want to learn more about the hows and whys of in-person payment orchestration – browse our FAQ here.

Ready to future-proof your business and stay ahead in PayTech?

Be prepared and strong with flexible, competitive solutions that keep you and your customers connected to a robust platform. If you also believe that in-person payment orchestration is the key – let's talk.

Interested in reading more around this subject? Here are some useful articles…